Why Forced Ranking is an Engine for Systemic Discrimination in the Workplace

Published on: November 24th, 2024

Rank and Yank: A Formal and Empirical Investigation

What is Forced Ranking and Why Should I Care?

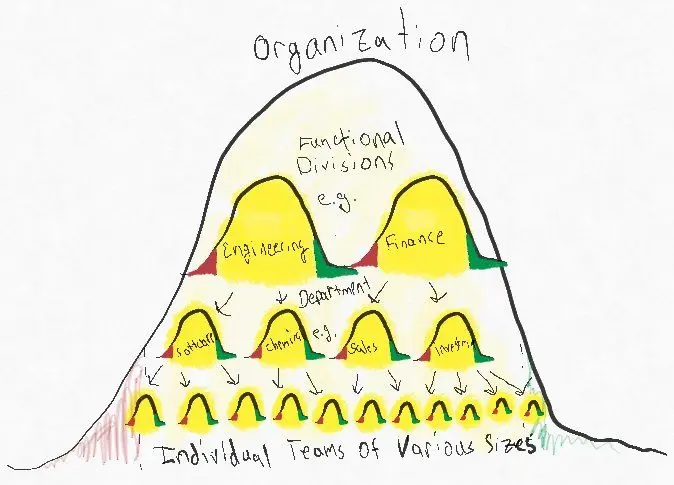

Forced ranking is, in essence, a performance management system that corporations use that is based on the bell curve, which has significant flaws that can perpetuate systemic biases. In this article we will argue that the forced ranking system is particularly damaging to those with invisible disabilities. Forced ranking, also known as stack ranking, or colloquially "Rank and Yank," requires managers across an organization to categorize their employees as underperforming, average, or overperforming based on fixed percentages. For instance, a company may enforce a curve where in each individual group 15% of employees must be labeled as underperformers, 75% as average, and only 10% as overperformers. The practice relies on several assumptions:

Forced ranking is, in essence, a performance management system that corporations use that is based on the bell curve, which has significant flaws that can perpetuate systemic biases. In this article we will argue that the forced ranking system is particularly damaging to those with invisible disabilities. Forced ranking, also known as stack ranking, or colloquially "Rank and Yank," requires managers across an organization to categorize their employees as underperforming, average, or overperforming based on fixed percentages. For instance, a company may enforce a curve where in each individual group 15% of employees must be labeled as underperformers, 75% as average, and only 10% as overperformers. The practice relies on several assumptions:

- It is assumed that the distribution chosen by the company's leadership is reflective of the underlying reality.

- we assume that it is a reality that the true distribution of performance will be 15% underperformers, 75% average and 10% high performers.

- It is assumed that even the smallest of teams will be representative of this distribution.

- Should we really expect statistical averages to apply to a team of five people?

This hierarchically enforced distribution means no matter how well a team performs, some individuals must still be deemed underperformers, and that strong performers may be placed into the average category if they work on a higher performing team. These rankings are then used to determine compensation and even layoffs and terminations. The specific distribution and number of categories in the ranking system can vary, as can the specifics of how they are implemented, but the one common factor that all forced ranking systems share is their codification of systemic discrimination into standard business processes.

There are other critiques of the forced ranking system which have been covered extensively in other articles, including actively discouraging teamwork and collaboration, a refocusing on hyper-individualism and personal achievement at the expense of team success, and high costs of hiring and retraining new employees who are not guaranteed to be any more productive than the ones who were removed. Microsoft used a widely internally criticized stack ranking system to manage their employee's performance which was credited by many as a reason for Microsoft's "lost decade," during Steve Ballmer's management when Microsoft missed out on many possibilities to innovate and grow, but stagnated due to poor strategic decisions and performance mismanagement.

'If you were on a team of 10 people, you walked in the first day knowing that, no matter how good everyone was, two people were going to get a great review, seven were going to get mediocre reviews, and one was going to get a terrible review,' said a former software developer. 'It leads to employees focusing on competing with each other rather than competing with other companies.' --Vanity Fair

The result was a focus on ensuring a positive ranking rather than genuine collaboration and innovation. Employees would strategically position themselves to work on weaker teams in order to increase their chances of receiving a favorable ranking. In Microsoft's system group managers would often have some level of flexibility to adjust distributions on their own team provided the umbrella group [group of groups] they were a part of with other group managers met the distribution. This assignment of ranking to employees (a process referred to by the corporate term "calibration"), which happened behind closed doors, resulted in the explicit prioritization of improving visibility, not only to an employee's own manager, but to manager's in adjacent groups as well, during an employee's performance review.

'I was told in almost every review that the political game was always important for my career development,' said Brian Cody, a former Microsoft engineer. 'It was always much more on ‘Let’s work on the political game’ than on improving my actual performance.'

This system was largely responsible for stifling Microsoft's ability to innovate for over a decade. There are real long term costs a company's decision to use this system of performance management, but a company may still use it as a measure to squeeze as much productivity as possible out of existing employees in a competitive economic environment, or to reduce headcount as an alternative to layoffs. Even in these cases, while forced ranking may accomplish the short term goal of the company, it will always perpetuate biases no matter how carefully the company crafts the system to avoid the outward appearance of bias.

The Necessity of the Ambiguous Performance Metrics Under a Forced Ranking System

Under a forced ranking system it is provably impossible to provide workers with clear and objective measures of success in their roles. The ambiguity of performance metrics under this system is a feature, not a bug. It allows the organization to adjust the rankings regardless of individual achievements, thereby maintaining control over the distribution of performance categories. When performance metrics are predetermined and clear, all employees can aim to meet them. But in a forced ranking system, it is structurally impossible for everyone to succeed, because someone must always be placed at the bottom, which unfortunately often results in enormous financial consequences or even job loss.

Let us briefly illustrate the paradox of attempting to define unambiguous performance objectives under a forced ranking system, which we will do by assuming the existence of a forced ranking system and attempting to articulate criteria of success in advance. Suppose for each employee a set of clear and objective performance criteria are defined. For an arbitrarily chosen employee at the company, once we have written down and formalized these criteria for success, it becomes possible for that employee to meet those criteria. Since we chose the worker arbitrarily, we are able to determine that it is possible for every employee to meet their criteria for success. If every employee meets these criteria, then logically none of them can be classified as underperformers. But we assumed we were operating in a forced ranking system which requires a certain percentage of employees to be labeled as underperformers, and that is a contradiction. This thought experiment demonstrates the impossibility of defining objective, unambiguous performance criteria for all employees, meaning that the criteria remain necessarily subjective and ambiguous.

Forced Ranking has Historically Been Used for Systemic Discrimination and Still Survives in Corporate Workplaces

Historically, forced ranking has been weaponized to push out older employees, resulting in class action lawsuits and settlements, such as the high-profile case against Ford Motor Company in the early 2000s, where forced ranking was linked to age discrimination. The system serves as a thin veil to codify bias into corporate culture. But it doesn’t just affect older workers. According to James Fett, who represented workers in their class action lawsuit against Ford Motor Company:

Whenever a forced ranking system could have an unequal effect on any group of workers, he says, “you’re asking for trouble—legally, and more importantly, in workforce morale and productivity.”

Jim Sykora, 56, who was let go from Goodyear Tire Company after multiple decades of good performamce reviews and more international patents than he count reflected on how after two rounds of forced ranking at his company "Suddenly I became a non-performer." Sykora suggests that if his performance was truly underperforming he should have received coaching rather than being immediately terminated. He was among a group of employees in a class action lawsuit against Goodyear alleging age discrimination in its performance review practices.

This kind policy, and the reliance on being able to prove "disparate impact" to challenge it legally, is particularly insidious for employees with invisible disabilities, including neurodivergent individuals such as those on the autism spectrum. Neurotypical people often harbor implicit biases against autistic individuals and form negative first impressions based on brief observations of social behavior. These biases result in reduced willingness to interact with autistic individuals, not because of the content of their interactions, but due to superficial style cues that differ from neurotypical expectations. The halo effect and the associated horn effect are well documented phenomena showing that "global evaluations of a person can induce altered evaluations of the person's attributes, even when there is sufficient information to allow for independent assessments of them." Forced ranking takes those intangible biases and transforms them into a quantifiable reason for termination. In effect, autistic people are professionally harshly punished for immutable characteristics of themselves. Many autistic people are acutely aware of this fact as the research has been highly publicized through books like Dr. Devon Price's "Unmasking Autism," and simply aligns with the lived experiences of many autistic people. They understand that such rapid evaluations lead to social stigmatization and exaggerated negative assessments of their competence based on nothing more than non-neurotypical behaviors. For this reason many autistic workers are forced to engage in exhausting "masking" behaviors. In the words of autistic advocate Kieran Rose

Masking is exactly what it sounds like, we put a mask on. A Neurotypical one. Those of you that have young children who are fine at school and Meltdown at home, have already witnessed it, as they are the ones who are especially good at it. Conforming at school is masking.

These behaviors include consciously suppressing "stimming," altering their communication style to be less direct, forcing themselves to make eye contact, creating elaborate scripts for use in conversations, and remaining in unfriendly sensory environments despite the fact that masking has been linked to poor mental health outcomes, relationship issues, and suicidality.

There is such a phrase in the Autistic Community as ‘Autistic Burnout’. If you’ve known adults both diagnosed or undiagnosed that have managed to live relatively “Normal” lives, you’ve probably witness it in them. They plod along, perhaps forging a good career in a stable job, then suddenly they’re promoted, their job changes, or they change jobs and the world falls out from under their feet. They can no longer cope. This is usually when the realisation happens that they are different, that they’ve spent their whole lives pretending. The mask slips away.

They may also refrain from disclosing their disability out of the very real fear that it would be used to discriminate against them. Unfortunately, this makes it difficult to prove a disparate impact under a forced ranking system.

Invisible disabilities, by their nature, are already difficult to prove in legal battles that rely on demonstrating a "disparate impact," which refers to practices that may be non-discriminatory in intention but result in a disproportionately negative effect on a protected group. Disparate impact cases typically require data showing that a certain policy disproportionately affects a protected group. For visible aspects of identity like race, gender, or age, gathering this data is relatively straightforward, but for disabilities like autism, which is severely underdiagnosed and underreported, especially in marginalized groups, the data is fragmented and incomplete. Many autistic individuals may never receive a formal diagnosis and can only resort to self-diagnosis due to barriers like the high cost of formal evaluation, a lack of trained clinicians who understand adult autism, and the prevailing stereotypes about what autism looks like. These individuals still face systemic biases, partially stemming from the thin-slice judgments previously described, but they are left without the necessary legal tools to advocate for themselves or contribute to cases that expose discriminatory practices. This, in addition to the pressure on diagnosed neurodivergent individuals not to disclose their disability clearly highlight how the forced ranking system targets a group that is already isolated and makes their marginalization an engrained feature of corporate policy.

The inherently subjective nature of forced ranking, combined with systemic undervaluation of neurodivergent communication styles, creates a workplace environment where autistic employees are disproportionately disadvantaged. Evaluations are often based on norms that have no bearing on job performance but instead reflect neurotypical social expectations, charisma or ease with small talk. These biases overshadow the unique strengths autistic individuals bring to the workplace, which can include intense focus, precision, and innovative problem-solving. For someone with an atypical focus style their ability to concentrate deeply can result in exceptional outcomes in tasks requiring sustained attention, like data analysis or quality assurance. Their detail-oriented mindset could be particularly valuable in roles requiring accuracy, such as software testing or research, and their unconventional thinking could foster creative solutions in complex scenarios. Unfortunately, these attributes are frequently dismissed while deficits in superficial traits that align with neurotypical norms are excessively penalized. The lack of transparency in forced ranking further compounds this inequity, as autistic employees are left unable to challenge or understand the basis of their evaluations. Research supports this, demonstrating that autistic individuals face significant bias in workplaces, with negative judgments often rooted in divergent social behaviors rather than actual competence or productivity. This system crushes the spirit of autistic workers and demands they erase their true selves to survive the corporate environment.

Forced Ranking Highlights the Need to Strengthen the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

This practice must end. Disabled and neurodivergent employees already face significant barriers in the workplace, with an often cited statistic stating around 80-90% of autistic individuals with college degrees are unemployed or underemployed. Forced ranking adds one more layer of inaccessibility by creating hostile work environments where biases are not just tolerated but systematized. The ambiguous performance metrics, unwritten rules, and non-collaborative environment fostered by forced ranking directly target the weaknesses of autistic employees, effectively functioning as an anti-accommodation. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) promises equal opportunity, but practices like forced ranking expose its weaknesses and limitations. While the ADA looks promising on paper, in practice it fails to protect against the systemic erosion of job security for disabled individuals.

To create truly inclusive workplaces, policies and practices must be reimagined to support neurodivergent employees, including those on the autism spectrum. Forced ranking systems are fundamentally incompatible with this goal. Research highlights that workplace accommodations, which can include providing sensory-friendly environments, clear communication, and flexible task management strategies improve job satisfaction, performance, and retention among autistic employees. Unfortunately those needing these accommodations cannot thrive in an environment driven by forced ranking, which actively penalizes differences rather than adapting to them.

A strengths-based approach, which emphasizes the unique abilities of autistic workers, offers a more equitable framework for evaluating employee contributions. Practices like job carving which entails customizing roles to align an individual’s strengths with organizational needs, demonstrate how tailoring tasks to neurodivergent workers strengths can benefit both employees and employers. These strategies require nuanced, individualized evaluation systems, which is the direct antithesis of forced ranking, which demands arbitrary quotas and exclusion for anybody falling outside of the norm.

The lack of transparency inherent in forced ranking creates a hostile environment for employees to disclose disabilities, something already difficult for neurodivergent workers. Disclosure is essential for these workers to receive accommodations but the stigma and fear of retaliation often discourage it. A workplace without forced ranking would be the first step toward enabling robust anti-discrimination policies and mentorship programs to flourish. These policies could open the door to open dialogue and mutual support among neurodiverse employees and their neurotypical peers. This environment would empower autistic individuals to self-advocate and contribute their strengths without fear of unfair evaluation or termination.

Ending forced ranking is a moral as well as a practical imperative. We must end this system of performance evaluation and replace it with systems that prioritize accommodation, transparency, and strength-based success criteria, which can allow workplaces to harness the full potential of their diverse workforces. Until neurodivergent workers are able to have clear, individualized performance metrics, reasonable accommodations, and bias training for managers, a workplace cannot be considered inclusive. Inclusive policies benefit everyone, not just neurodivergent individuals. They encourage innovation, collaboration, and a deeper sense of belonging among all employees. It's time to end outdated corporate practices that punish employees for their differences, deny them the opportunity to contribute their unique skills and talents, and degrade their quality of life. The workplace must be a place where all can thrive.